Collision between German Navy Ironclads

Grosser Kurfürst and König Wilhelm

The Illustrated London News June 8, 1878

The Collision off Folkestone. Sinking of a German Ironclad.

Another terrible naval disaster has proved the dangers that, even in time of peace, attend the modern construction of enormous war-ships. The sinking of H.M.S. Vanguard by collision with

her consort the Iron Duke, in the Irish Sea, three years ago, was, happily, not accompanied with any loss of life. Upon the present occasion, we have to deplore the untimely death of nearly as

many seamen, belonging to a foreign national service, as perished lately in the English crew of H.M.S. Eurydice, from an accident of a somewhat different kind. The German Ironclad turret-

ship, Grosser Kurfürst (the 'Great Elector'. meaning the Brandenburg Prince who was the founder of the kingdom of Prussia) was sunk off Folkestone by collision with a ship of the

same squadron, the König Wilhelm, on the Friday of last week. Two hundred and eighty four of her men were drowned, or perhaps some of them were scalded to death, as her steam-boilers

seem to have burst while she sank, which took place within about nine minutes. We are enabled, by the aid of correspondents who saw this fearful occurrence, and by the sketches

made immediately afterwards, to give several illustrations. These include a small plan, to show the course taken by the squadron of three vessels, the König Wilhelm, Admiral's flagship, the

Grosser Kurfürst, and the Preussen, just before the collision. It will help to explain the manner in which the two first-mentioned ships came to strike against each other with such fatal effect.

The German squadron of evolution, commissioned on the 6th ult. for service in the Turkish waters or the Levant, if political affairs should require, was composed of three turret-ships, the

Grosser Kurfürst, the Preussen, and the Friedrich der Grosse, and the powerful Ironclad König Wilhelm, which was the flag-ship of Admiral von Batsch, commanding the squadron. The

Friedrich der Grosse, indeed had not yet joined the squadron while cruising in the British Channel. The König Wilhelm, which was commanded by Captain Kuhace, is the largest

Ironclad in the German navy. She was originally designed by Mr. E. J. Reed, C.B., M.P., when at the Admiralty, for the Sultan of Turkey, who himself determined the length of the ship, by fixing

it at 365 ft., or one foot for each day in the year. The name of the ship was at that time the Fetikh, and her construction was begun under the supervision of Mr. Reed and his overseers,

at the Thames Ironworks, Blackwall. After a short time, the Turkish Government found it inconvenient to continue payment of the instalments as they fell due upon the ship, and

accepted an offer for her purchase for the German Government. The construction and fitting of the ship were then withdrawn from English supervision, and placed under the care of German

overseers, during the remainder of the building and fitting of the ship. The name was also changed to that of König Wilhelm. An Illustration of this ship was published in our journal at

the time of her completion. The ship is, as above stated, 365 ft. in length, 60 ft. in breadth, and has a draught of water of 26 ft., with a tonnage displacement of 9600 tons. She has engines of

1150 nominal, and 8300 indicated, horse-power, by Mandalay and Co. She has armour 10 in thick and carries an extremely powerful battery, consisting of eighteen 14 1/2-ton guns upon

the main-deck, and five 9-ton guns upon the upper deck. She is a rigged ship with a most formidable ram-bow. It will be seen from these particulars that the Konig Wilhelm is one of the

most powerful seagoing ships in the world. The other two ships which formed part of the squadron last week in the Channel - namely, the Preussen and the Grosser Kurfürst - were

vessels of only about two thirds the size, and much inferior to her both in offensive and defensive power.

They were armoured seagoing turret-ships, very similar in design to H.M.S. Monarch, and fully rigged. These turret-ships, as well as the König Wilhelm, could steam at the rate of fourteen

miles an hour. The Grosser Kurfürst was constructed at the Wilhelmshaven Dockyard, and launched in 1875. Her dimensions were as follows:- Length between perpendiculars, 307 ft.;

extreme breadth, 52 ft.; depth in hold 23 ft.; her draught was 24 ft., and her extreme displacement 6663 tons. The hull was divided by transverse bulkheads into twelve watertight

compartments. She carried four 10-inch Krupp rifled guns in her turrets, and a couple of 6 3/4-inch Krupp guns on her deck. The thickness of her armour was 9 in. at the water-line and 7 in.

on the sides, while the iron walls of her turrets were 10 in. in thickness. The backing varied from 10 in. at the water-belt to 1 ft. on the sides. The nominal horse-power of her engines was

850. The commander of the Grosser Kurfürst was Captain Count Montz, who formerly served in the British Royal Navy. The total complement of officers and men belonging to this

unfortunate ship was 500, but three had been left behind at Wilhelmshaven.

The morning of yesterday week, unlike the day on which the Vanguard was sunk by the Iron Duke, was favoured with clear weather, with a light easterly wind blowing down Channel and a

perfectly smooth sea. The German squadron of three vessels at the time of the accident was sailing in two columns, the König Wilhelm, with the flag of Admiral von Batsch, and the

Preussen, forming the port-division, with the Grosser Kurfürst forming the starboard division. The German Admiral was leading the port division : in a British naval squadron he would have

led the other. This, however, makes no essential difference, except that in hugging a coast a British Admiral would probably prefer the inshore line for his own ship. But the essential

difference in the formation of the squadrons is that the German columns are at all times considerably less than half the distance apart that is thought advisable for British ships, and in

many instances even much nearer to each other. Thus, the Grosser Kurfürst was within less than two ships' length of the König Wilhelm, bearing slightly abaft the beam. This was her

nominal bearing and distance: but in reality she was even nearer, and probably not more than one length intervened between the two ships. In this formation the German squadron came

across two sailing-vessels hauled to the wind on the port tack, and consequently standing across the bows of both divisions. The Grosser Kurfürst had first to give way, which she did at

the proper time, and strictly in accordance with the rule of the road, porting her helm and passing under the stern of the first of these two merchantmen. But the König Wilhelm, which

was close to the Grosser Kurfürst at this time, and steering a course parallel to her, endeavoured at first to cross the bows of the merchant-vessel, but, finding she had no room

for this manoeuvre, rapidly changed her course, and, putting her helm hard-a-port, also stood under the stern of the merchant-barque. Meanwhile, the Grosser Kurfürst had resumed her

original course, and was thus lying right across the bows of the König Wilhelm as she came under the stern of the sailing barque almost at right angles to the original course. At this

critical moment the two ironclads were in dangerous proximity to one another, and it became an impossibility for either the one or the other to sheer out of the way. The captain of the

Grosser Kurfürst, seeing the terrible proximity of the König Wilhelm, immediately put his vessel at full speed, hoping to cross her bows, but the space would not allow it. He then gave the

order to port his helm, hoping to lay his ship parallel to the course of the König Wilhelm; but unfortunately for this also there was neither time nor space, and the only effect of the helm

must have been that the stem of the Grosser Kurfürst, swinging rapidly towards the approaching danger, must have contributed to the force of the shock.

The officer in charge of the König Wilhelm had given the order to port the helm to sheer clear of the sailing-vessel. He immediately ordered the helm to be steadied when he saw his vessel

clear, with the intention of ranging up alongside the Grosser Kurfürst in their former position. But the helmsman was bewildered, and instead of steadying the helm and putting it to

starboard, gave her still more port helm. The König Wilhelm's officer, seeing the inevitable collision before him, promptly gave the order to reverse the engines; and it is said that the

engines were actually going full speed astern at the moment of the collision. But it is not in the power of engines to stop a ponderous vessel, weighing some 9000 tons and gliding at the

speed of ten knots through smooth water, in so short a space. The Grosser Kurfürst was going nine or ten knots, and the König Wilhelm at least five or six. The actual shock was very

slightly felt on board the König Wilhelm, though it did great damage to her bows. The shock on board the Grosser Kurfürst was felt far more. The ship lurched heavily on the opposite

side, while a crushing and tearing sound filled the air as the stem of the König Wilhelm sheered away everything from the point where she struck to the stern, ripping off the armour plating

like the skin of an orange. The blow came at an angle variously described as somewhere between a right angle and an angle of forty-five, and caught the Grosser Kurfürst between the

main and mizen masts. The Grosser Kurfürst, from the speed she had attained, was barely checked in her course by the collision, but grated past the stem of the König Wilhelm, leaving a

vast gap in her side. The bowsprit of the König Wilhelm fouled her rigging and brought down the mizen-topgallant mast on the quarter-deck. The quarter boats were swept away, and the

doomed ship first staggered over on the opposite side from the force of the blow, and then reeled back, when the sea rushed into the great hole in her side. Below water all must have

been destroyed, for the ram of the König Wilhelm gives deadly indication, by the injuries it has received, of the work it did underneath.

On board the Grosser Kurfürst there was little or no time for anything. The boats on one side were smashed, and those on the other could hardly be got into the water; as the ship was lying

on one side, and, the other side being uppermost, the boats merely lay on the bottom or side of the ship. The hammocks had, unfortunately, been stowed in some unusual place between the

boom-boats, as the nettings were being cleared out: so that it was useless to attempt to get them out, and thus a means of escape was withheld from many poor fellows who were

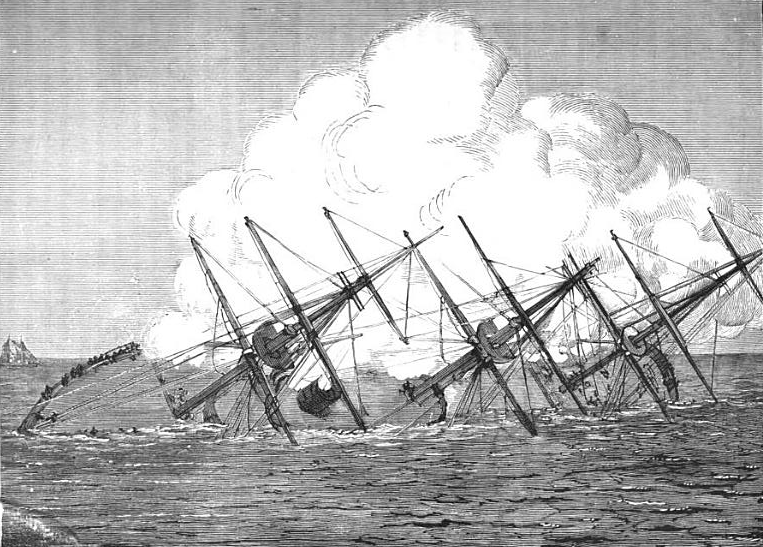

drowned. The ship for a very few minutes swung round and made a circle inshore, and lay with her deck exposed to the view of the people on the beach at Sandgate. It appears to have

been the intention of the captain to beach his ship immediately, but this was impossible even at the high rate of speed at which he was going. The water poured down the stokehole, the

steam from the condenser escaped, the stokers were driven up the hatches, and some few escaped up the steps which lead up inside the ventilators. It is uncertain whether the

compartments were closed, though the captain issued orders to that effect. But from the first moment it was evident that nothing could be done to save the ship. Lying altogether on her

port side, it was merely a matter of minutes, as the equilibrium was lost and the water poured in everywhere. In six or eight minutes, according to different witnesses, the vessel entirely

disappeared, sucking down in the vortex many of the crew who have been saved, and many who perished.

The first Lieutenant says that he felt himself sucked in and a sensation of enormous pressure on his ribs, as if the water was forcing him down. Then he appeared to come across another

column of water which vomited him up to the surface, where he caught hold of a spar and saved his life. The Captain also went down, but came up again and was saved. The officer of

the watch was drowned. There were some thirty of the sailors who, in spite of the commands and entreaties of the boatswain, standing on the forecastle, threw themselves over the bows

and endeavoured to swim away. But the ship was sinking too fast for them, and they were caught in the netting which is stretched under the jibboom, and, thus entangled, were carried

down with the ship. The whole number who perished was 284: there were 216 picked up, including twenty-three officers, while six officers lost their lives. Three of the men picked up

have since died of exhaustion.

Four of the side boats, cutters, gigs, and one launch were in the water from the König Wilhelm in a very few minutes, while the Preussen also sent every boat to render assistance. As the

König Wilhelm began to settle by the head from the water in the fore compartment, the Admiral at first intended to beach her, but after a short time, seeing that the pumps were able to keep

the water down to a safe level, he abandoned the idea. The Preussen in the meanwhile anchored, and her boats were busy picking up any men still afloat they could find; these,

however, were very few.

In the course of the afternoon the two vessels proceeded to Portsmouth, and on arriving the König Wilhelm was immediately docked. The appearance presented by her bow is shown in

one of our Illustrations. This is a large rent, through which the sea rushed in and immediately filled the fore compartment. This compartment is in a line with the armour-plated bulkhead,

forward, and extends to the double bottom. The valves were shut, but probably were a little leaky, as a good deal of water found its way further aft. The ship, by the loss of equilibrium,

gave an unexpected plunge or two, which must have been extremely alarming, and the highest praise is due to all on board that discipline was not only maintained, but that every effort was

made to render assistance to their unfortunate consort.

The ram of the König Wilhelm has certainly proved most effectually destructive, but at the same time, it has demonstrated the weakness of its own construction. Viewed from the bottom

of the dock, the ram and portion of the stern itself are seen to be twisted over to the port side at an angle of 45 deg., and the bottom plating and the armour above gapes wide open from within

a few feet of the keel to the upper-deck, all the rivets (tapped rivets) which secured them to the stem being, in shipbuilding parlance, sheared - that is, the heads drawn through the holes or

broken off short. The armour-plating terminating at the armour-shelf has left the stern by shearing off the rivets, and the stern itself is broken short off at the armour-shelf, and also at its

scarf, some six feet below the ram.

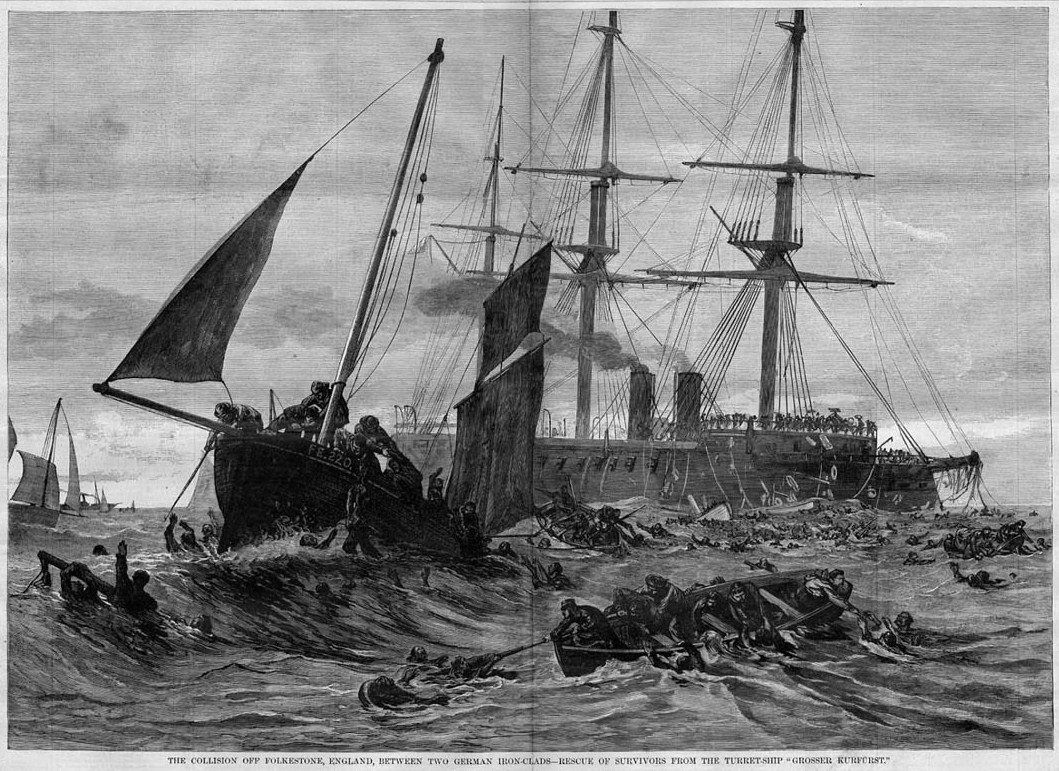

Two of our Illustrations, one representing the squadron, with the merchant-barque, just before the collision, and the other showing the Grosser Kurfürst sinking, with her consorts near her,

are supplied by sketches taken by an eye-witness, Lieutenant R. Rudyard, of the 39th Regiment. He was standing on the beach at Sandgate, superintending a firing squad of

soldiers, and saw the ships alter their position and the König Wilhelm and Grosser Kurfürst get close together; the latter then detached herself from the former, and turned towards the shore,

but heeled over on one side. She paused a minute, then fell over and sank, a large jet of steam rising from her as she went down. It was so sudden, that a soldier who was firing a shot, and

who noticed the ship heel over as he raised his rifle, looked up just after firing, and the ship was gone. The König Wilhelm had lost her bow-sprit, and was settling down at the bows,

which seemed much damaged.

The Folkestone fishing-boats, especially the Emily Richard, which picked up twenty-seven men, were instrumental in the rescue of many survivors, to the number altogether of eighty-five. Our large

Engraving (the Extra Supplement) was drawn with the assistance of Mr. May, the master of the Emily Richard, and is a faithful representation of this subject. We are indebted also to the Thames

Ironworks Company for some assistance in drawing the Illustrations of the damage to the König Wilhelm, but a sketch was made of her bows and ram in the dock at Portsmouth.

The recovered bodies were buried in the Cheriton Road cemetery, and a large memorial stands there today in memory of those who lost their lives that day.